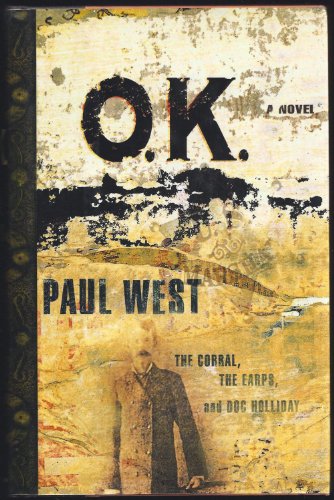

Items related to Ok: The Corral The Earps And Doc Holliday A Novel

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Sweet old nightshade, his mind whispered as he lurched across the saloon, bumping other drinkers but intent on leaning over the spittoon to make a vertical shot. Not for him the sleek parabola or the deadeye straight line between two points. He hardly wanted to be seen, which was never true of him in his bright seemly days back in the postbellum South before being told when he was twenty-one how sick he was. No one here saw a dull red blob fall from his lips into the mouth of the cuspidor, not even making it resound faintly, and nobody cared among that ravenous, besotted rabble. Doc was part of the scenery, alive, doomed, or dead. Now the old wonder-worry began of what was he doing there; was this all he had been born for? Poker, faro, killing, and haughty buckaroo justice meted out with an erratic hand and a good aim? Here he was, pretending to be several kinds of men, mingling with killers and desperadoes, far from chiming Chopin pressed into sound by his thick muscular fingers, and fine judicious reading, from the Bible to -- well, by now he had forgotten the names of the poets he used to read. He even read some Latin. What had drawn him into the stark company of the Earps? His familiarity with death? His ability to sum up his lived life in the teeth of all the days he was going to be dead and all those days he had remained unborn? Who then had urged him to move westward in search of a better clime in which to breathe, as if breath were a tournament of hard icicles in copper-plated lungs? The Earps' closeness to death had echoed his own, he thought, as once again, many times hourly, its raw shadow limped across the buoyant outline of his heyday, one day soon to take him and dust him away as if he had never been. Or, he wondered, did he keep on playing dangerously in the hope of forestalling the reaper's knock? Ida Pempest had urged him, that was who, she of the spoken spittle and the beefy legs.

Having advanced from sobersides good citizen to playboy, then onward into gunplay addict and glowering death-fancier, Holliday had become an incontinent figure in certain saloons whose gaming tables drew him in like fragments of some holy grail: chance writ large as mediocre heraldry. He pondered, as ever, the spectacle of himself, simply pleased but sometimes even awed that he could be going downhill, up and down Boot Hill, so completely, becoming a man who, the more his lungs wore out, the more he needed to lunge in on other lives. It was a poor bargain, he decided, worthwhile to some other man maybe, less educated than himself, less of a funereal cavalier, but skewed, shameful, almost as if he Holliday were bucking for attention from popular novelettists of the times, to whom Earps were bread and butter. He winced at being himself so much and resolved to do better, though lacking anyone to model himself after. The horrors of being unique in Trinidad and Leadville, Cheyenne and Deadwood, made him wish he had stayed a gullible boy gnawing on a toothpick in pseudo-masculinity, hoping never to be caught out in greenstick maundering, aping other boys while wondering how anyone could come into this world without a blueprint, a clear direction to go in, even a clearly defined road to hell. Was this what Earp provided, then? That old question, nagging at him daily, making him sure of himself even while he went on trembling and his mouth, like that of any dental patient, went on filling with blood? Doc Holliday shook his head at himself, trapped in the tenseless tension of his day-to-day, doing something irrevocable every second, unable ever to draw back from the vast ongoing suck of life, patron of all sweet atoms as they rose and fell.

How had it gone when he rode into Jacksboro, Texas, in '72? Right there at the edge of town had been an oldish bald man carpentering coffins, who looked up at the stranger riding in and called as if in greeting, "Five foot eleven, I'm never wrong, mister. Be seein you." At that Holliday had drawn and threatened to blow the man's brains out, miming the whole performance as he rode slowly through the uplifted fan of the other's gaze, the pair of them held hard in mutual disdain. Then he was past and he holstered his gun, thanking the gods for the reassuring smack of metal against his palm. He was not a killer yet, although a premonition of that status gnawed at him somewhere deep inside as he advanced westward toward health, noting how behavior got more and more boisterous, more final and absolute, as if the Devil had come home to roost. Doc didn't mind this gross declension, rescuing him as it did from the poor fate of becoming a fop, done up in pale blues and satin grays, nattily crafted suits and cravats tied like roses. It had not taken him long, torn as he was between the dandyism of the Southern dentist and the clinking leathers of the Western shootist, to decide how to dress for his journey and indeed all the years afterward (as he thought): in a long gray coat closed at the neck, like a clergyman gone to seed, though perhaps a gravedigger or a sexton would have dressed thus as well. Already he was Doc Holliday rather than Dentist Anyone, an unkind intervener, a confident man who, if he ever made the time, would write an autobiography entitled Left to My Own Devices, an epic of lordly whim. Airs and graces he had left behind him in the land of sly gentility, and now he figured on that harsh and arid landscape as of no more significance or consequence than a mosquito on a naked calf of a leg, setting up its unique filtration circus. Early on, he had developed the knack of ridiculing himself just to keep from getting too uppity with the wrong folks (such as the instantly measuring coffin crafter), and would keep things that way, mildly insinuating himself into that or this limb of society until he could bear to show himself off, sponsoring gunplay. In short, as he saw it, he was a hell of a prospect who, once he got himself launched in a dry climate, would soon become a somebody to be reckoned with, taut and stern and no huge respecter of human life. Going out to infect or infest the prairie, he reveled in the prospect of himself, born to elegance, graduand in deviltry, not so much a self-made man as one self-destroyed and ravished by the process of his own decay. How many souls he took with him on his deadly swoon he cared not, provided they did not haunt him in the afterlife. He would be happy to be thought of as accursed, maldito, self-abused into rotting bravado.

I, he mused, am very much a man of blood, fancy as that sounds. I am at home with it and its pumps, its pomps. I am an invader, coughing disease all over the West after having polluted the South, forcing that metallic-acrid aroma of blood into the mouths of who knew how many willing patients.

He thrilled to be so decisive about himself, knowing how women recoiled from his breath and then became accustomed to its fruit-of-death bouquet as if his very saliva were the manna of orgasm and, when he came, he came red or frothy pink, spluttering with it as if God had first choked him on it and then told him to relieve himself. Rougemont, he murmured, that might be my name; sometimes, I am red's rider.

What he had learned had not been much, but he had absorbed something precious that told him an abiding truth. Early in life, he had found, the battle was with other students, with memory and manual demands, examiners and resisting teeth, all a matter of smarts and qualification. You were always sticking your head in the sand for safety's sake only to expose to the world the parts you did your thinking with. All that was behind him, kind of, at twenty-one; the battle, henceforth, was with mortality, hardly a competition like that in medical school, or for the hand of some Southern belle sans merci whose mouth prefigured, modeled, that other slimy workbench of nature he had first discovered when he was twelve. Whatever he managed to bring off from now onward would have to be ranked opposite death, compared with it, measured against it, tested against it, which ennobled whatever he did. It was like testing a burp against a tornado, all out of proportion of course, but huge and insolent. How many men have you killed compared with how many death had? The very idea gave him potent shivers even as he recognized the nonlogic in the thought. Death was not a competitor but, if you could bear the thought, an ally, a goal, a prize. Surely that was how to think if you happened to be, as he, spoiled, ripe for plucking, a youth dwindling into a fated man, swapping a dental tool for a six-gun in the hope of some infernal reprieve, so much death's that death spared him.

Here he came again, the overmotivated young adventurer, heading west by stagecoach and horse to save his life, confident of the outcome and thus unable to sever the expedition from greenstick notions of savorship. Something exalted preyed on him and supplied a carnal thrill that almost replaced lust or fantasy; he was not leaving the South merely to make a living, to get rich, he was en route to a resurrection that would take him to ninety and beyond, into the flaming new century. When the truth emerged, as he awoke daily or settled down to sleep, the cough always racking him, he was the young explorer gone sadly wrong, exchanging visionary milk and honey for a superlative wasteland on which nothing grew, ran, or cried. It was hard for him to come up with an attitude that responded fully to having failed to save his own life, doing that very thing each day without the faintest idea of what to do next other than go farther, taking his blight with him.

Where, oh where, were the sanatoria he had heard about, mostly in alpine climates, where sufferers lay on long chairs in leaky sunshine, wrapped in furs and quilts, inhaling the frost that (he thought) slaughtered the bacillus? They were in his mind, defunct idylls, denied him by some mishap of geography. So he would be unable, either, to fall in love on an elegant veranda facing a partly frozen lake, with another consumptive of course, forbidden to kiss, or even to breathe upon each other, but mentally enraptured while their lungs teetered. Where had he acquired the notion that, if things went wrong, they went wrong late, in doddering dotage with a whole other generation on hand to help out? Here he was, an invalid in early manhood, uselessly trekking from one place to another in quest of some accidental angel who would purge him of disease overnight and swoop away with him, offering him career and fortune with the same glad hand, and love's delicate conflagration to boot. Not only did it not bear thinking about; it made him wonder if losing an impromptu gunfight wasn't the best way out, under the roasting sun, in the eyeteeth of a screaming blizzard. All he needed was an end, which he would then attach to his life with disconsolate brio as if brio were glue.

Hence, for him, the interchangeability of all places. One after another they came and went, or rather he came to them and left them, staying when he stayed like a trapped insect, moving on when he did so with weak-willed callowness. There was no compass to this ride, only a journey up and down like the mercury's in the thermometer with no way out, never mind how far his eyes could see over the tight-stretched drumskin of Kansas, say. After a while he began to understand that he did not need an attitude to the spiritual inanity that had overtaken him. He thought of surrendering himself to a monastery in which to spend his last few years in a rough black or brown habit, waiting for the final spasm; but he dismissed the notion in favor of what he came to call his floating fury.

How he longed for the days, not long ago, when he aimed that imitation six-gun and made explosive sounds with his mouth: kisk, kisk, after which triumphant smoke curled from the barrel commemorating accuracy's kiss. It had been the same when he rode into Jacksboro; the gun had been fully loaded, but the shots had been pretend. He wanted to head back into the gulch of the make-believe, where Wyatt Earp was only a myth and the Latin that Doc quoted was dog Latin, all fake, far from country-dentist erudition. The point-down triangle of his bandanna folded double was something else he wanted to revoke; had he actually held up the Benson stage, a masked man with sullen good manners, asking them to stand and deliver like the Dick Turpin of old, back in the old country? English highwayman, subject of legends, the book had said, not Doc Holliday, American consumptive, subject of make-believe. Had he ever shot open a strongbox and then kept the box as a spittoon, closing its lid when visitors came by? What had he done with all that scratch? All that blood? Had he really carried old dental tools in a leather bag, telling folks he kept them for torturing people with? They jangled as he lurched and formed new patterns when he jerked to cough. It was never enough to arrive in a saloon, ask for a bed and a bottle; his needs were more elaborate than that. Most of all he needed an audience, not to talk to, but to watch him as he retched and then wiped tears from his eyes, the tears he called neutral because they had no feeling behind them save that of discomfort. A tin cup perched on a chipped plate was never enough either, though he had made do in many a saloon and lean-to. "None of your beeswax," he had said a thousand times when he asked for some decent crockery, an unencrusted fork, and they had wondered none too civilly what he was being so fussy about. Had he once worn an india-rubber jacket guaranteed to keep the cold out, but not the lead slung at him by those who hated the cut of his jib, as he nautically called it?

It must have been the dentist, doctor manqué, in him that noticed as no one else seemed to the constant wailing of women in those Western towns, the canker sores, the cold sores, the boils and styes. Something was wrong with everybody without their ever needing to handle poisonous snakes or drink full-strength strychnine, or, more privately, inhale the noxious odors of a severed head kept in isinglass like an egg, to ward off evildoers and encourage sanctity when hung on a pulpit. He had not seen everything, but he had seen too much without, ever, managing to stitch it all together into what he might have been able to call a social code, a mode of life, a tissue of unruly habits. It was not his way to integrate, but to leave disparate phenomena be, refusing to call a million grains anything so united as sand. To him, experience was an addition, a forever ongoing process with nary a sum at the end, enabling him to live (as he wished) from incident to incident without thinking either to death.

He was a chameleon, then, and had often heard that word applied to him, even thinking back to his first train journey from Georgia, when he undressed in a sleeping car so cramped it felt like undressing under a bed. Three berths high, the overnight accommodations held all three of him (the hothead, the aesthete, the dentist) in suffocating proximity. That night in Kimball's sleeping cars, which took him only as far as Chattanooga, did little to calm him for the odyssey -- Memphis, New Orleans, Galveston, Dallas -- that followed. He had the paralyzing sense that Amer...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2000

- ISBN 10 0684848651

- ISBN 13 9780684848655

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Ok: The Corral The Earps And Doc Holliday A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks167054

OK: THE CORRAL THE EARPS AND DOC

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.03. Seller Inventory # Q-0684848651