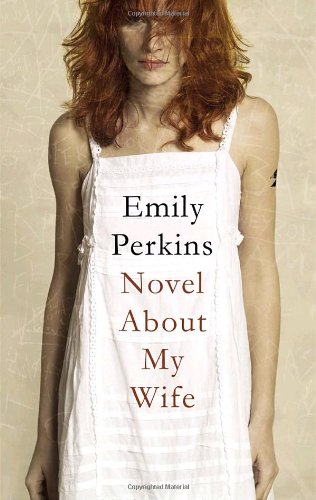

Items related to Novel About My Wife

From one of Britain’s most exciting young writers comes the story of a couple’s emotional and complicated relationship ... from the husband’s perspective. Novel About My Wife is narrated by Tom Stone as he searches through the mysteries his wife has left him with. The reader is left to discover what dark thing has come between him and his beloved partner.

Tom Stone is, as well as being cheerfully neurotic, madly in love with his wife Ann, an Australian in self-imposed exile in London. Pushing forty and newly pregnant, they buy their first house in Hackney. It seems they are moving into a settled future, despite spiralling money troubles. But Ann is dogged by a local homeless man whose constant presence comes to feel like a terrible omen. As her pregnancy progresses Ann finds solace in her new friendship with Kate, a woman Tom is both repelled by and peculiarly drawn to. Their home is beset with vermin, smells and strange noises. Is this normal for London, or is the measure of normality in this city actually mad?

Novel About My Wife is Tom’s effort to understand this woman he has been so blindly in love with, and to peel back the past to see where the real threats in their lives were hiding. It is an investigation of guilt, love, forgiveness, and the perils of forgetting.

She wasn’t one of those women who hate their feet, who hate their bodies, the kind who turn the sight of their ass in broad daylight into a state secret. (God, you just find yourself dying for a glimpse, you’ll do anything to get it, hover outside the bathroom door, hide under a table, pull back the sheets when she’s sleeping. Then because of all the mystery you end up, when you’re finally feasting your eyes, thinking, ‘hey, maybe she has got something to worry about.’) Ann didn’t care. Her body was open for viewing. It was one of the ways she distracted you from what was inside her head.

--from Novel About My Wife

Tom Stone is, as well as being cheerfully neurotic, madly in love with his wife Ann, an Australian in self-imposed exile in London. Pushing forty and newly pregnant, they buy their first house in Hackney. It seems they are moving into a settled future, despite spiralling money troubles. But Ann is dogged by a local homeless man whose constant presence comes to feel like a terrible omen. As her pregnancy progresses Ann finds solace in her new friendship with Kate, a woman Tom is both repelled by and peculiarly drawn to. Their home is beset with vermin, smells and strange noises. Is this normal for London, or is the measure of normality in this city actually mad?

Novel About My Wife is Tom’s effort to understand this woman he has been so blindly in love with, and to peel back the past to see where the real threats in their lives were hiding. It is an investigation of guilt, love, forgiveness, and the perils of forgetting.

She wasn’t one of those women who hate their feet, who hate their bodies, the kind who turn the sight of their ass in broad daylight into a state secret. (God, you just find yourself dying for a glimpse, you’ll do anything to get it, hover outside the bathroom door, hide under a table, pull back the sheets when she’s sleeping. Then because of all the mystery you end up, when you’re finally feasting your eyes, thinking, ‘hey, maybe she has got something to worry about.’) Ann didn’t care. Her body was open for viewing. It was one of the ways she distracted you from what was inside her head.

--from Novel About My Wife

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Emily Perkins was born in New Zealand in 1970. She is the author of the short story collection Not Her Real Name, which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize and was shortlisted for the John Lewellyn Rhys Prize, and the novels Leave Before You Go and The New Girl. She lives in New Zealand and London with her husband and three young children.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

If I could build her again using words, I would: starting at her long, painted feet and working up, shading in every cell and gap and space for breath until her pulse just couldn’t help but kick back in to life. Her hip bones, her red knuckles, the soft skin of her thighs, her fine crackle of hair. (That long red hair. The shock of it spread out on the floor.) I loved her boredom, her glazed look, her dark laugh, her eyes. The way she moved around things, gliding, very near. The warmth that emanated from her skin. Everybody gives up warmth but with Ann it had a special quality, as though she was heat seeking heat, threatening to touch you in the spirit of danger, on a dare. She’d stand in the gutter, off the kerb, while she was waiting to cross the road. Buses skimmed past. She didn’t flinch.

She wasn’t one of those women who hate their feet, who hate their bodies, the kind who turn the sight of their ass in broad daylight into a state secret. (God, you just find yourself dying for a glimpse, you’ll do anything to get it, hover outside the bathroom door, hide under a table, pull back the sheets when she’s sleeping. Then because of all the mystery you end up, when you’re finally feasting your eyes, thinking, ‘hey, maybe she has got something to worry about.’) Ann didn’t care. Her body was open for viewing. It was one of the ways she distracted you from what was inside her head.

And her feet weren’t perfect: they were long and dry, with knobbly toes and a verucca on one heel which never went away because she refused to do anything but laugh about it. She liked pedicures, massage, that slightly sickening world of female self-obsession, and went in for toenail polish in dark, back-off shades. The lightning bolt scar on her right arm was a bubble-edged disaster, a memento of her youth that she kept covered up. What you couldn’t take your eyes off were her legs. She had a sexy stance and walk, sort of hollow around the waist and jutty at the hips, shoulders slumped forward. Now that I see it written down it makes her sound like a gorilla, but was more sort of slutty flapper. Bear with me.

She was a mould-maker; that was her job, to take casts of people’s bodies, the parts of their bodies that were ill and needed radiating to kill cancer cells or shrink tumours. This wasn’t what she’d had in mind during her sculpture major at the Slade but it brought its own satisfactions. A little plaster-dusted room at St Bartholomew’s hospital very like a studio, the Hogarth diorama she could visit there each day, the walk to work under St John’s Gate. She loved the historical location, the feeling it gave her of being part of something, of belonging. It was a raggle-taggle version of the past that Ann had, she picked up scraps about the Knights Templar or pilgrims, 18th century pleasure gardens, I don’t know, there was no grand scheme in her mind, no connecting dots. She was not an intellectual; she had a scattershot approach to knowledge. And she needed the feeling of stone at her back, even if it was in ruins.

I can’t look at Ann in terms of the bare bones. She was this kind of person, she was that. Her parents were whatever, the house she grew up in was blah — it isn’t going to work. Partly because there’s so much I don’t know. It was Ann’s mystery I fell for, her genuine mystery, not the cultivated kind so many of the English girls had. Those girls, I can give you their bare bones: Mummy and Daddy still together, decent schools, hopes of working in television, a pesky brush with the law over shoplifting, an affair with a drug dealer, a lost night waking into a frightened morning (where am I, what is that mark on the floor, I don’t even have tube fare, where the fuck are my jeans) that is better left unexcavated and so she puts the bad-girl days behind her. She flounders for a bit. Drops the media dream and retrains, funded by the parents, in something useful to society (can’t think what that might be), in which instance she is out of my orbit and we’ll never cross paths again. Or pursues the dream with renewed vigour, pulls contacts to get a job on the women’s section of a broadsheet supplement, acquires a new edge, drops the milliners and jewellery designers that she went to school with and goes out to bands at night. Then she meets me, or someone like me, at the launch for a new short film and bang. A few movies, a Malaysian meal or two, the introduce-to-friends dinner party, three months of electric fucking, one midweek trip to a foreign city and then the writing on the wall. They’re paper, those girls, and Ann was flesh.

I’d like to be inside her somehow, to strap her ribcage on over my own and see the world from behind her skin like the serial killer in a lurid film. Breathe with her breath, hear and smell with her senses, taste the inside of her mouth. Speak with her voice. A clear Perspex mask of her head, big holes gaping for eyes and mouth, sits in the corner of my office. She had a radiotherapy trainee do it, lay the cling film over her face, cover her with the cold gypsoma strips, piece by tightening piece — so she would understand how her brain tumour patients feel. Plaster has plastic memory. Ann found it magical. These aren’t death masks, she’d say, they are the opposite. I borrowed her glassy head for one of my creatures, back when I was trying to please Alan Tranter, trying to go commercial. Now I want more than this transparent mould from Ann; want to make her so real that I can hold her. Hish — quiet. Shut off the radio. Close the window on the neighbours, muffle those clangouring workmen in the street below. I’m trying to hear her speak. It isn’t going to be easy, for a man more used to writing about vampires than about spirit, flesh and blood. But I’d like to know what the hell else I’m meant to do. I don’t know how to remember her.

*

A long time after the accident, as though she was experiencing déjà vu, Ann swore that she had dreamt about it — being on the derailed train — before it happened. I couldn’t tell if this was true or whether she was trying, after the event, to turn what was really a disturbing memory into a premonition of some kind — into something with meaning. Why she would do that was a mystery, but by that stage I didn’t know why she would do or say a lot of things. ‘It was dark,’ she said, as though seeing a warning film playing in her head, ‘but emergency fluorescents flickered, lighting the passengers in odd blues and yellows. There was the toasty smell of smoke or burning hair. Most people stayed calm. We followed the instructions that came over the tannoy system.’ When she spoke she still sounded like herself. She’d kept her careful, covered-over accent.

‘All of us walking forwards over the rails towards the next stop felt, some people said at the hospital later, a weird feeling of achievement, camaraderie, the pleasure of an ordeal survived. You knew that it was better to be down there, in the hot dark mess of it all, than being one of the thousands of passengers whose journey was delayed. All above your head were men and women with nothing to show for it. You could imagine them, taking the spiralling stairs up from Covent Garden, late for meetings and lunch dates, travellers bound for Heathrow banging suitcases hundreds of steps, no money for taxis, losing their holidays, no way now of catching their aeroplanes out.’ Ann’s eyes were glassy. She was on holiday from herself; she didn’t need an aeroplane.

When she was thrown from her seat to the other side of the underground train, hitting her head on the yellow metal pole, Ann’s first thought was for the baby. The lights went out and a sharp object jabbed her in the temple (it was the corner of another woman’s briefcase) and she realised she wasn’t being attacked but that something had gone wrong. ‘This is it! This is it!’ shouted a female voice and she thought, don’t be so stupid, of course it’s not. Then through the darkness she smelled smoke and quickly felt it stinging her eyes, robbing her, for the moment, of her remaining vision, and she wondered if perhaps the hysterical woman was right. Ann was three months pregnant with our baby, that astonishing baby, and I assumed she had left work early so as to miss rush hour: she’d been feeling sick, headachey and exhausted, but because she didn’t yet show nobody knew to give up a seat for her on a crowded train. Londoners do give up seats on trains, despite what other people think of us. I made a habit of it after the morning when Ann phoned me from work, her voice bumpy like she was saying the words aloud for the first time, which she was. She had been pregnant before, but not to me; not to anybody she would tell.

And there she had been in her carriage, sitting on the worn tartan cover of the bench seat, where a billion tired, impatient, resigned people had sat before, coming home early, so I thought, because she was in need of comfort, in need of rest. Earlier at Farringdon station, waiting for the train to arrive, she watched two immigration officers approach a couple of men who were speaking to each other in some kind of Arabic. One of the men started to walk away and an officer followed him, stepping around and into his path so he couldn’t go forward. For a few seconds they performed a ludicrous dance, until the man took a wallet from his jacket and shoved it into the immigration officer’s face. ‘I really resent this,’ he said in a loud, accented voice, gesturing so that everyone near him on the platform turned to look. ‘Papers, he wants, here they are.’ The officer made a point of looking methodically through the wallet, his face expressionless. ‘All in order?’ the foreign man asked as he shoved the wallet back inside his su...

She wasn’t one of those women who hate their feet, who hate their bodies, the kind who turn the sight of their ass in broad daylight into a state secret. (God, you just find yourself dying for a glimpse, you’ll do anything to get it, hover outside the bathroom door, hide under a table, pull back the sheets when she’s sleeping. Then because of all the mystery you end up, when you’re finally feasting your eyes, thinking, ‘hey, maybe she has got something to worry about.’) Ann didn’t care. Her body was open for viewing. It was one of the ways she distracted you from what was inside her head.

And her feet weren’t perfect: they were long and dry, with knobbly toes and a verucca on one heel which never went away because she refused to do anything but laugh about it. She liked pedicures, massage, that slightly sickening world of female self-obsession, and went in for toenail polish in dark, back-off shades. The lightning bolt scar on her right arm was a bubble-edged disaster, a memento of her youth that she kept covered up. What you couldn’t take your eyes off were her legs. She had a sexy stance and walk, sort of hollow around the waist and jutty at the hips, shoulders slumped forward. Now that I see it written down it makes her sound like a gorilla, but was more sort of slutty flapper. Bear with me.

She was a mould-maker; that was her job, to take casts of people’s bodies, the parts of their bodies that were ill and needed radiating to kill cancer cells or shrink tumours. This wasn’t what she’d had in mind during her sculpture major at the Slade but it brought its own satisfactions. A little plaster-dusted room at St Bartholomew’s hospital very like a studio, the Hogarth diorama she could visit there each day, the walk to work under St John’s Gate. She loved the historical location, the feeling it gave her of being part of something, of belonging. It was a raggle-taggle version of the past that Ann had, she picked up scraps about the Knights Templar or pilgrims, 18th century pleasure gardens, I don’t know, there was no grand scheme in her mind, no connecting dots. She was not an intellectual; she had a scattershot approach to knowledge. And she needed the feeling of stone at her back, even if it was in ruins.

I can’t look at Ann in terms of the bare bones. She was this kind of person, she was that. Her parents were whatever, the house she grew up in was blah — it isn’t going to work. Partly because there’s so much I don’t know. It was Ann’s mystery I fell for, her genuine mystery, not the cultivated kind so many of the English girls had. Those girls, I can give you their bare bones: Mummy and Daddy still together, decent schools, hopes of working in television, a pesky brush with the law over shoplifting, an affair with a drug dealer, a lost night waking into a frightened morning (where am I, what is that mark on the floor, I don’t even have tube fare, where the fuck are my jeans) that is better left unexcavated and so she puts the bad-girl days behind her. She flounders for a bit. Drops the media dream and retrains, funded by the parents, in something useful to society (can’t think what that might be), in which instance she is out of my orbit and we’ll never cross paths again. Or pursues the dream with renewed vigour, pulls contacts to get a job on the women’s section of a broadsheet supplement, acquires a new edge, drops the milliners and jewellery designers that she went to school with and goes out to bands at night. Then she meets me, or someone like me, at the launch for a new short film and bang. A few movies, a Malaysian meal or two, the introduce-to-friends dinner party, three months of electric fucking, one midweek trip to a foreign city and then the writing on the wall. They’re paper, those girls, and Ann was flesh.

I’d like to be inside her somehow, to strap her ribcage on over my own and see the world from behind her skin like the serial killer in a lurid film. Breathe with her breath, hear and smell with her senses, taste the inside of her mouth. Speak with her voice. A clear Perspex mask of her head, big holes gaping for eyes and mouth, sits in the corner of my office. She had a radiotherapy trainee do it, lay the cling film over her face, cover her with the cold gypsoma strips, piece by tightening piece — so she would understand how her brain tumour patients feel. Plaster has plastic memory. Ann found it magical. These aren’t death masks, she’d say, they are the opposite. I borrowed her glassy head for one of my creatures, back when I was trying to please Alan Tranter, trying to go commercial. Now I want more than this transparent mould from Ann; want to make her so real that I can hold her. Hish — quiet. Shut off the radio. Close the window on the neighbours, muffle those clangouring workmen in the street below. I’m trying to hear her speak. It isn’t going to be easy, for a man more used to writing about vampires than about spirit, flesh and blood. But I’d like to know what the hell else I’m meant to do. I don’t know how to remember her.

*

A long time after the accident, as though she was experiencing déjà vu, Ann swore that she had dreamt about it — being on the derailed train — before it happened. I couldn’t tell if this was true or whether she was trying, after the event, to turn what was really a disturbing memory into a premonition of some kind — into something with meaning. Why she would do that was a mystery, but by that stage I didn’t know why she would do or say a lot of things. ‘It was dark,’ she said, as though seeing a warning film playing in her head, ‘but emergency fluorescents flickered, lighting the passengers in odd blues and yellows. There was the toasty smell of smoke or burning hair. Most people stayed calm. We followed the instructions that came over the tannoy system.’ When she spoke she still sounded like herself. She’d kept her careful, covered-over accent.

‘All of us walking forwards over the rails towards the next stop felt, some people said at the hospital later, a weird feeling of achievement, camaraderie, the pleasure of an ordeal survived. You knew that it was better to be down there, in the hot dark mess of it all, than being one of the thousands of passengers whose journey was delayed. All above your head were men and women with nothing to show for it. You could imagine them, taking the spiralling stairs up from Covent Garden, late for meetings and lunch dates, travellers bound for Heathrow banging suitcases hundreds of steps, no money for taxis, losing their holidays, no way now of catching their aeroplanes out.’ Ann’s eyes were glassy. She was on holiday from herself; she didn’t need an aeroplane.

When she was thrown from her seat to the other side of the underground train, hitting her head on the yellow metal pole, Ann’s first thought was for the baby. The lights went out and a sharp object jabbed her in the temple (it was the corner of another woman’s briefcase) and she realised she wasn’t being attacked but that something had gone wrong. ‘This is it! This is it!’ shouted a female voice and she thought, don’t be so stupid, of course it’s not. Then through the darkness she smelled smoke and quickly felt it stinging her eyes, robbing her, for the moment, of her remaining vision, and she wondered if perhaps the hysterical woman was right. Ann was three months pregnant with our baby, that astonishing baby, and I assumed she had left work early so as to miss rush hour: she’d been feeling sick, headachey and exhausted, but because she didn’t yet show nobody knew to give up a seat for her on a crowded train. Londoners do give up seats on trains, despite what other people think of us. I made a habit of it after the morning when Ann phoned me from work, her voice bumpy like she was saying the words aloud for the first time, which she was. She had been pregnant before, but not to me; not to anybody she would tell.

And there she had been in her carriage, sitting on the worn tartan cover of the bench seat, where a billion tired, impatient, resigned people had sat before, coming home early, so I thought, because she was in need of comfort, in need of rest. Earlier at Farringdon station, waiting for the train to arrive, she watched two immigration officers approach a couple of men who were speaking to each other in some kind of Arabic. One of the men started to walk away and an officer followed him, stepping around and into his path so he couldn’t go forward. For a few seconds they performed a ludicrous dance, until the man took a wallet from his jacket and shoved it into the immigration officer’s face. ‘I really resent this,’ he said in a loud, accented voice, gesturing so that everyone near him on the platform turned to look. ‘Papers, he wants, here they are.’ The officer made a point of looking methodically through the wallet, his face expressionless. ‘All in order?’ the foreign man asked as he shoved the wallet back inside his su...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBond Street Books

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0385662246

- ISBN 13 9780385662246

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 169.70

Shipping:

US$ 31.90

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Novel About My Wife

Published by

Bond Street Books

(2008)

ISBN 10: 0385662246

ISBN 13: 9780385662246

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. New. book. Seller Inventory # D7S9-1-M-0385662246-6

Buy New

US$ 169.70

Convert currency